As ten days of UN-sponsored climate talks came to end in Bonn, Germany on Thursday morning, global campaigners demanding far-reaching solutions to the crisis of a warming planet expressed dissatisfaction on multiple levels, charging that the continued foot-dragging of governments is sentencing future generations to unparalleled catastrophe even as scientists issue grave new warnings about the dangers of inaction.

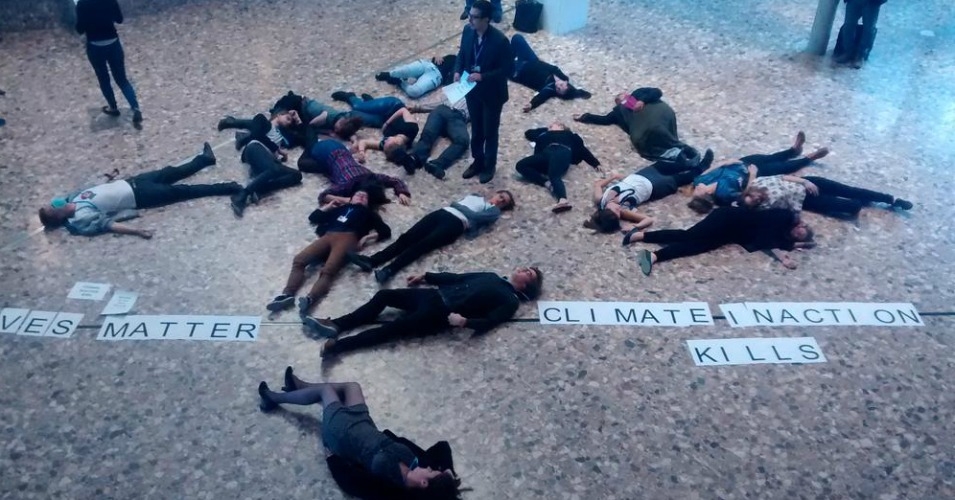

As the final sessions concluded and the latest draft texts emerged from the talks, activists staged protests inside and outside of the convention center calling for bold action on climate and an “energy revolution” that would steer the world away from coal, oil, and gas and towards renewable sources like wind and solar.

“Climate change is upon us, and every increase in temperature causes more heatwaves, droughts and floods, killing thousands of people,” Cadena said. “If developed country governments continue to drag their feet at the UN negotiations instead of taking immediate action, millions of people will pay for it with their lives. People around the world are already implementing real, proven solutions—community-controlled, renewable energy systems. The energy revolution has come of age, and our politicians must help implement it or fade into obsolescence along with the dirty energy systems they cling to.”

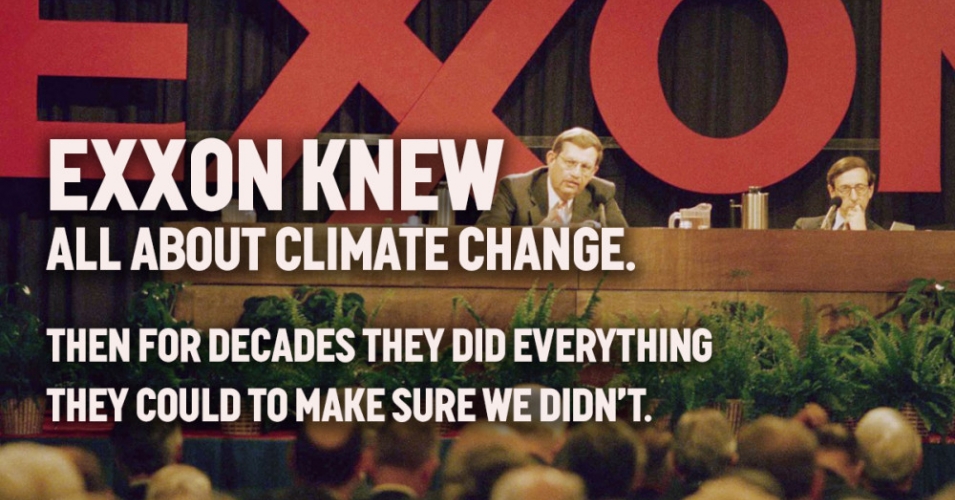

Payal Parekh, the managing director for 350.org’s global climate campaign, said that though the negotiations are moving too slow on key issues, it is becoming increasingly clear that the status quo is untenable. “Negotiators need to pick up the pace,” Parekh said. “The climate talks are still catching up with a new political reality–one where the fossil fuel industry is losing its stranglehold on our economy. Coal is already on the way out, and oil and gas must follow. The surging divestment campaign is changing the game, and the movement for climate action will only grow ahead of Paris.”

Among the key issues that climate justice advocates say remain inadequately addressed: ambitious and binding emission-reduction targets for all nations, and the continued refusal of the most-developed nations to contribute financially to mechanisms that would see lesser-developed nations—where the people least responsible for climate change live—be compensated for the “loss and damage” they have suffered and will continue to experience in the future. As Gita Parihar, head of the legal team at Friends of the Earth-UK, explained in a blog post from Bonn, “This harm is becoming an everyday reality for developing countries, even though they are not responsible for the emissions causing it.”

And as Harjeet Singh, a campaigner for ActionAid, explained, “Africa, small island states and the least developed countries have unequivocally demanded that ‘loss and damage’ be part of the Paris deal. Even if we have 100% renewable energy by 2050, the impacts will continue for another 100 years. The Paris deal has to tackle the increasing climate damages, and not just the causes.”

In a separate blog post, Singh expanded on this idea:

Rich nations, in particular the United States, Canada, Japan and Australia, have been brushing off the demands of developing countries and civil society to act according to their responsibility for and fair shares of planet-warming emissions.

For decades, they neither reduced greenhouse gas emissions at home, nor provided adequate resources to developing countries to transform their energy systems and build resilience.

Future mass-scale litigation by developing countries in the International Court of Justice is not an impossibility.

Demanding compensation and reparations for the loss and damage caused due to rich nations’ inaction remains the only pivot to hold them to account. It will also drive action on mitigation and provide timely resources for adaptation to prevent further loss and damage.

“Negotiators avoided a show-down over crunch issues like finance and increasing near term emissions cuts, but they are only delaying the inevitable,” said Jan Kowalzig, the climate change policy adviser for Oxfam International. “The G7 have set a powerful vision of a fossil fuel free future, but this is at odds with their limited ambition to reduce emissions in the short term. They also need to bring developing countries on board by being clear that developed countries will be first movers in the fossil fuel phase out, as well as by putting financing on the table to enable them to follow suit.”

And when it comes to temperature targets, observers of the Bonn talks are again lamenting the flimsy nature of the commitments made. Though world governments have previously agreed to keep global temperatures from rising more than 2°C this century, experts say that target is not possible given current trends or what nations have been willing to put on the table in terms of emissions cuts. As Bill McKibben, co-founder of 350.org, wrote at Grist on Thursday, “At the moment [world leaders] look set to ratify a global temperature increase of 3 or 4 degrees C — that is, to lock us into a kind of slow-motion guaranteed catastrophe.”

Speaking of catastrophe, the Bonn talks were also the scene of new climate warnings from the scientific community, including from researchers who have been looking closely at the threat of frozen methane-hydrates, currently trapped in the world’s layer of permafrost. If unleashed, these methane-hydrates could trigger a severe greenhouse gas and climate feedback loop. As Agence France-Presse reported this week:

There may be 1,500 billion tonnes of carbon locked away in permafrost—perennially frozen ground covering about a quarter of exposed land in the Northern Hemisphere, said Susan Natali, a researcher with the Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts.

The carbon will be released incrementally as global temperatures rise on the back of soaring emissions from mankind’s voracious burning of fossil fuels, making permafrost a vast and underestimated source of future greenhouse gas emissions, said Natali.

“By 2100 we expect 130 to 160 gigatons of carbon released into the atmosphere,” Natali told journalists in Bonn. “That is on par with our current rate of US emissions as a result of fossil fuel and cement production.” […]

The amount of carbon stored in permafrost, where it has accumulated over tens of thousands of years, is estimated to be about twice as much as that in the atmosphere, she said.

Speaking on the sidelines of the Bonn talks, Natali told AFP, “The actions that we take now in terms of our fossil fuel emissions are going to have a significant impact on how much permafrost is lost and in turn how much carbon is released from permafrost.”

She added, “While there is some uncertainty, we know that permafrost carbon losses will be substantial, they will be irreversible.”