As we are all aware, we are scheduled to receive for our review a Draft EIS from FERC covering the proposed Jordan Cove LNG Export terminal sometime later this year. There appears to be significant confusion and uncertainty within our community regarding the purpose and intent of a Federal EIS and the role we, as affected citizens, are expected and entitled to play in the process.

This paper is an effort to clarify the situation so as to facilitate our citizen’s review of the Draft EIS.

BACKGROUND

Prior to 1970, decisions made by Federal agencies regarding significant plans or projects were based primarily on social, economic, and technical factors. Environmental considerations, if they played any role at all, were commonly afterthoughts often resulting in feeble and ineffective attempts at mitigation.

In the Federal sector, this all changed in 1970 with the implementation of the National Environmental Policy Act, commonly referred to as “NEPA”. This Act specifically instructs all Federal agencies, boards, and commissions to “insure that environmental amenities and values are given appropriate consideration in decisionmaking along with economic and technical considerations”. NEPA procedures are intended to insure that environmental information is available to both public officials AND CITIZENS before decisions are made and before actions are taken.

NEPA also created the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), placed it within the Executive Office of the President, and charged it with overseeing NEPA implementation by all Federal agencies.

CEQ issued the first set of comprehensive implementing regulations in 1978. Since that time, CEQ has issued supplemental guidance and interpretation from time to time to clarify the requirements and applicability of various provisions of NEPA. The latest supplemental guidance from CEQ was issued on March 6, 2012.

This latest guidance from CEQ stresses several points, such as:

- NEPA documents should be straightforward and concise reviews and documentation that convey the relevant considerations to the public and decision makers in a timely manner. The NEPA process shall be integrated into project planning rather than be an after-the-fact process that justifies a decision already made.

- EIS’s are to be written in plain language and follow a clear standardized format. The text of a final EIS that addresses the purpose and need, alternatives, affected environment, and environmental consequences of each alternative should normally, even for projects of unusual complexity, be less than 300 pages in length.

- Federal agencies should explore every opportunity to integrate the process of meeting requirements of NEPA with other Federal agencies that are involved in a group of actions directly related to each other because of their functional interdependence or geographical proximity.

The purpose and intent of NEPA was challenged very quickly after its implementation. In a case filed against the Atomic Energy Commission in 1971, the DC Circuit Court of Appeals issued a landmark ruling that stated:

:

- The procedural duties imposed by NEPA are to be carried out by the federal agencies “to the fullest extent possible”. “This language does not provide an escape hatch for foot-dragging agencies; it does not make NEPA’s procedural requirements somehow ‘discretionary’. Congress did not intend the Act to be a paper tiger”.

- “Section 102 of NEPA mandates a careful and informed decision-making process and creates judicially enforceable duties. The reviewing courts probably could not reverse a substantive decision on the merits, but if the decision were reached procedurally without consideration of environmental factors -conducted fully and in good faith- it is the responsibility of the courts to reverse.”

In spite of clear legislative and regulatory intent, recent administrations have gone to great lengths to evade full compliance with NEPA. Especially troubling is the increasing necessity of citizen groups having to turn to the federal court system in order to uphold existing environmental laws. Citizens faced with unresponsive agencies and a hostile legislative branch are left with little choice but to demand in court that they be provided with the information and analyses, in a standardized and understandable format, to which they are entitled under NEPA. The situation is perhaps best described by the following quotation which appeared in the Duke University Environmental Law Journal: “Even a cursory review of the record reveals the pattern of an administration looking to change environmental law by fiat, collusion, and deception. These changes have little regard for environmental consequences and even less regard for the foundational democratic principles of transparency and open debate”.

We have two recent examples pertinent to our area that illustrate attempts by Federal agencies to circumvent the requirements of NEPA.

The most recent was the EIS for the Jordan Cove Import terminal which was followed immediately by the issuance of an implementing permit. The issuance of the permit was immediately challenged on the basis of failure to meet NEPA requirements by the Oregon Attorney General as well as a consortium of environmental groups. Rather than contest the allegations of failure to comply with NEPA, FERC quickly vacated the permit. This led, of course, to the current situation wherein we await the issuance of a new Draft EIS for what has now become the Jordan Cove Export terminal proposal.

Another example is provided by the BLM Western Oregon Plan Revision for the management of the O&C timber lands. This multi-year multi-million dollar effort remained in effect for about one year until it was withdrawn as being “legally indefensible” because of its failure to comply with the spirit and intent of NEPA and the Endangered Species Act.

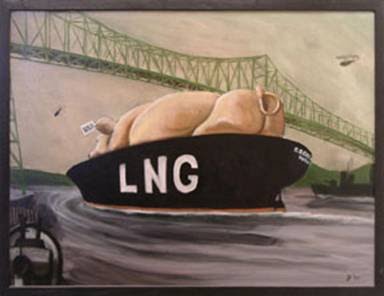

The proposed Jordan Cove Export terminal could have massive effects, both positive or negative, short-term and long-term, on the social, economic and environmental aspects of our area. Thus, it is absolutely critical that we, as concerned citizens, demand that FERC’s EIS fully provides us with the data, information, and analyses to which we are explicitly entitled under NEPA and related judicial findings.

REVIEWING THE DRAFT EIS

To make sure that all Federal agencies comply with the National Environmental Policy Act, the Act itself includes an “action-forcing” mechanism that requires them to prepare an environmental impact statement (EIS) for all plans and projects that could have significant environmental effects. An EIS must be objectively prepared and not slanted to support the choice of an agency or an applicant’s preferred alternative over the other reasonable and feasible alternatives.

It is most important to recognize that a Draft EIS for Jordan Cove is not meant to be a decision document. Rather, it is the first stage of a three-step process which ultimately leads to a decision.

Step one is the issuance of the DEIS followed by a time period during which members of the public may submit their comments relating to the adequacy and viability of the data collected and analyzed. Following this is step two which is the publication of the final environmental impact statement (FEIS). All substantive public comments received on the DEIS are to be attached to the FEIS along with the agencies response thereto. Following another public review period, step three takes place. This results in a record of decision (ROD) being issued which identifies all alternatives considered by the agency and documents how it balanced the effects of the social, economic, and environmental effects of each in reaching its final decision.

NEPA regulations are quite specific as to what information, and in what format, we are entitled to receive in the EIS. Agencies are urged to use the “standard format for EIS’s” unless there is a compelling reason to do otherwise. To facilitate your review, following below is a synopsis of what NEPA and its implementing regulations require Federal agencies to include in each section of the standard format.

Before getting into the sections of the standard format, and by way of orientation, following is a synopsis of how existing regulations address the overall role and function of an EIS:

- An EIS should “…serve practically as an important contribution to the decisionmaking process and will not be used to rationalize or justify decisions already made”. (40 CFR 1502.5)

- An EIS “is more than a disclosure document. It shall be used by Federal officials in conjunction with other relevant material to plan actions and make decisions.” (40 CFR 1502.1)

- An EIS is meant to document how, specifically, environmental considerations were incorporated with economic and technical considerations in all plans and projects (NEPA 102A)

- An EIS “must be objectively prepared and not slanted to support the choice of the agency’s preferred alternative over the other reasonable and feasible alternatives”. (CEQ 40?, #4c.)

- An EIS “should be analytic rather than encyclopedic”. (40 CFR 1502.2a)

Following is a synopsis of existing regulatory requirements for each of the standard format sections:

1. PURPOSE AND NEED FOR THE PROPOSED ACTION

NEPA Requirements

An EIS should “specify the underlying purpose and need to which the agency is responding in proposing the alternatives including the proposed action” (40 CFR 1502.13)

An overview (programmatic) EIS “may be particularly useful when similar actions, viewed with other reasonably foreseeable actions, share common timing or geography”. For example, when a series of new energy projects are planned in an area, “an area-wide EIS would serve as a valuable and necessary analysis of the affected environment and the potential cumulative impacts of the reasonably foreseeable actions under that program or within that geographical area.” (CEQ 40?, #24b)

2. ALTERNATIVE WAYS TO MEET THE IDENTIFIED NEED

NEPA Requirements:

An EIS must examine all reasonable alternatives to the proposal. The emphasis is on what is “reasonable” rather than on whether the proponent or applicant likes or is itself capable of carrying out a particular alternative. Reasonable alternatives include those that are practical or feasible (emphasis in original) from the technical and economic standpoint and using common sense, rather than simply desirable (emphasis in original) from the standpoint of the applicant (CEQ 40?, #2a).

The EIS “must be objectively prepared and not slanted to support the choice of the agency’s preferred alternative over the other reasonable and feasible alternatives (CEQ 40?, #4c).

“The degree of analysis devoted to each alternative in the EIS is to be substantially similar to that devoted to the ‘proposed action’ “ (CEQ 40?, #5b).

The section of an EIS covering Alternatives “is the heart of the environmental impact statement. It should present the environmental impacts of the proposal and the alternatives in comparative form, thus sharply defining the issues and providing a clear basis for choice among options by the decisionmaker and the public. In this section agencies shall:

Rigorously explore and objectively evaluate all reasonable alternatives.

Devote substantial treatment to each alternative considered in detail including the proposed action so that reviewers may evaluate their comparative merits.

Include reasonable alternatives not within the jurisdiction of the lead agency or the applicant.

(40 CFR 1502.14).

3. AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT

NEPA Requirements:

The EIS “shall succinctly describe the environment of the area to be affected by the alternatives under consideration” (40 CFR 1502.15)..

4. ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES

NEPA Requirements:

“This section forms the scientific and analytic basis for the comparisons (of the alternatives including the proposed action) (40 CFR 1502.16).

“This discussion will include the environmental impacts of the alternatives including the proposed action “(emphasis supplied) (ibid).

“The ‘environmental consequences’ section should be devoted largely to a scientific analysis of the direct and indirect environmental effects of the proposed action and of each of the alternatives. It forms the basis for the concise comparison in the ‘alternatives’ section” (emphasis supplied) (CEQ 40?, #7).

The Environmental Consequences section is “An analysis of the impacts of each alternative on the affected environment, including a discussion of the probable beneficial and adverse social, economic, and environmental effects of each alternative (emphasis supplied) (Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, “Streamlining NEPA”, January 9, 2007).

RECORD OF DECISION

NEPA Requirements

“Preparation of an EIS is done in two stages, resulting in a draft and final EIS. Once the final EIS is approved and the agency decides to take action, the agency must prepare a public record of decision (ROD). CEQ regulations specify that the ROD must include a statement of the final decision, all alternatives considered by the agency in reaching its decision, …” (CRS Report for Congress: Streamlining NEPA, January 9, 2007, pg.11).

“Agencies shall adopt procedures to ensure that decisions are made in accordance with the policies and purposes of (NEPA). (40 CFR 1505.1)

“each Agency shall prepare a concise public record of decision. The record shall….Identify all alternatives considered by the agency in reaching its decision, specifying the alternative or alternatives which were considered to be environmentally preferable (emphasis supplied) (40 CFR 1505.2b).

“An environmental impact statement is supposed to inform the decisionmaker before the decision is made.” (CEQ 40?, #34b)

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS:

It is critical to the long-term health and well-being of our area that we each take the time to review and comment on the Draft EIS for the Jordan Cove Export project when it is issued. As you undertake your review, keep the following questions in mind:

- Does it comply with the purpose and intent of the NEPA regulations summarized above?

- Has it overlooked any social, economic, or environmental considerations or information that you are aware of?

- Does it attempt to justify a pre-determined decision?

- Does it slant the analyses to favor a pre-selected alternative?

- Does it include all elements of the proposal, including the changes to the 7.3 mile long Coos Bay waterway, the access channel and marine berth, the transfer pipeline, and the South Dunes power plant?

- Responding to a draft EIS is not the time to attempt to vote for or against the proposal. Rather, it is time to demand that we get the comprehensive and objective analysis to which we are entitled under Federal law.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Council on Environmental Quality, Executive Office of the President, “Regulations for Implementing the Procedural Provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act”‘ 40 CFR Parts 1500-1508, July 1, 1986.

http://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/NEPA-40CFR1500_1508.pdf2. Council on Environmental Quality, “Forty Most Asked Questions Concerning CEQ’s National Environmental Policy Act Regulations”, Federal Register Volume 46, No. 55, 18026-18038, March 23, 1981.

http://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/G-CEQ-40Questions.pdf3. Council On Environmental Quality, “Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA: Having your voice heard”’ December, 2007.

4. Executive Office of the President, Council on Environmental Quality, Memorandum for Heads of Federal departments and agencies, Subject: “Improving the Process for Preparing Efficient and Timely Environmental Review under the National Environmental Policy Act”’ March 6, 2012.

Let’s not forget that the import proposal EIS was obviated before opponents could rip it to shreds. (It was full of holes.) I’m willing to bet Jordan Cove will attempt to use that as its basis in this EIS so opponents might have an advantage in that regard. Read carefully, friends.

Thanks Mr. Sadler for educating the people. It’s sad that our elected professional politicians, local, state and federal choose to keep the people in their grasp by assuring the confusion. Of course, when challenged, we get – there is so much information out there and I wish that I could inform the people. Then hoping that we the people go back to sleep, they disappear.